A recent paper uses nucleation-assisted microthermometry and other techniques to date the deposition of amethyst in geodes in Uruguay. They suggest formation at temperatures of less than 100°C which is quite low.

Nucleation-assisted microthermometry is a technique used in geology to study the formation conditions of minerals. It involves analysing fluid inclusions within minerals. Fluid inclusions are tiny pockets of fluid trapped inside a mineral during its formation.

Nucleation-assisted microthermometry allows researchers to estimate the temperature and pressure conditions during the formation of minerals. This technique can be explained as follows:

Fluid Inclusions: These are small amounts of fluid trapped within a mineral as it forms. They can provide valuable information about the temperature and pressure conditions during mineral formation.

Nucleation: This refers to the initial process where a small number of atoms or molecules arrange in a pattern characteristic of a crystalline solid, forming a site upon which additional particles are deposited.

Microthermometry: This technique involves heating or cooling the fluid inclusions to observe changes in their physical state (e.g., melting or boiling). By doing so, scientists can determine the temperature at which these changes occur.

The other techniques employed were:

Determination of Triple Oxygen Isotopes, a method that measures the ratios of three isotopes of oxygen.

Cathodoluminescence Microscopy that involves the emission of visible light from a solid material when it is irradiated by an electron beam. This technique is used to study the luminescence characteristics of minerals and rocks, providing valuable information about their composition and formation history. It can reveal internal textures, zonal growth, and trace element distribution within minerals, which are not discernible using conventional microscopy.

Hydrogeochemistry, the study of the chemical properties and quality of groundwater and its relationship with the local geological environment. It involves understanding how water interacts with minerals and rocks, the dissolution of minerals, and the weathering of silicate and carbonate rocks.

And finally, a technique NOT employed by the researchers, Isotopic Luminescence Spectroscopy (ILS).

Isotopic Luminescence Spectroscopy (ILS) is an innovative technique that combines the principles of isotopic analysis and luminescence spectroscopy to study the formation and alteration processes of minerals and rocks. This method involves the excitation of mineral samples using a controlled light source, causing them to emit luminescence. The emitted light is then analysed to determine the isotopic composition of specific elements within the sample. To explain the benefits of ILS:

By analysing the luminescence spectra, ILS can determine the isotopic ratios of elements such as oxygen, carbon, and sulphur within the mineral. This provides insights into the geochemical processes that influenced the mineral’s formation.

ILS can reveal the conditions under which minerals formed, including temperature, pressure, and the presence of specific fluids. This helps geologists understand the geological history of a region.

The technique can also detect changes in isotopic composition due to alteration processes such as weathering, hydrothermal activity, or metamorphism. This information is valuable for reconstructing the post-formation history of minerals.

ILS can be used to study the impact of environmental changes on mineral deposits, such as the effects of acid rain or pollution on carbonate rocks. This has implications for environmental monitoring and protection.

By combining isotopic analysis with luminescence spectroscopy, Isotopic Luminescence Spectroscopy (ILS) offers a powerful tool for geologists to gain deeper insights into the complex processes that shape our planet’s mineralogy and geological features.

You may not have heard of any of the above techniques. But even if you have heard of some or most, you will have never heard of Isotopic Luminescence Spectroscopy, as it is fictitious. Totally made up. Compared to the other techniques though, I think it is quite believable! 😆

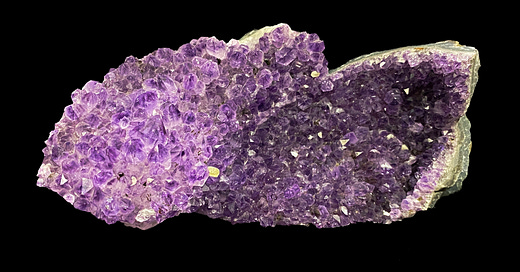

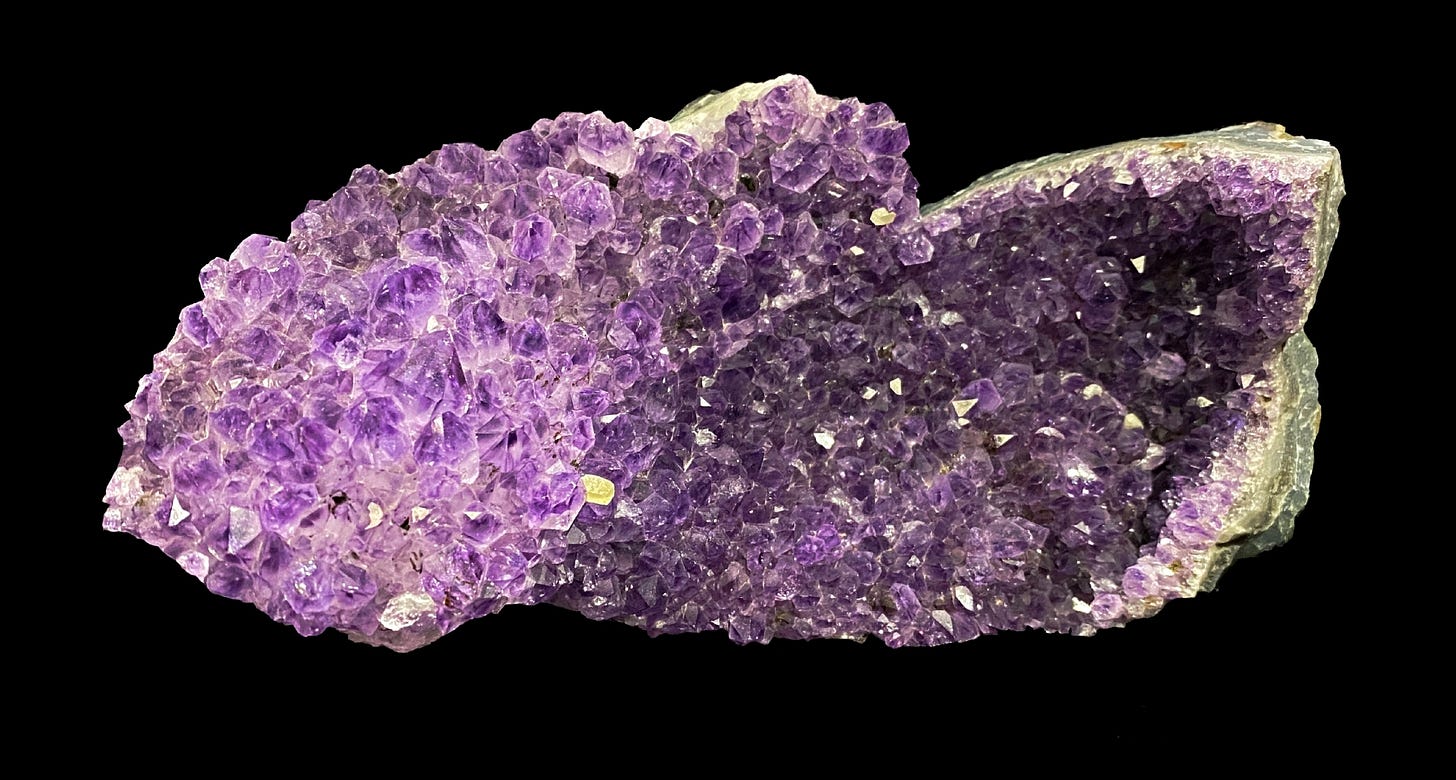

Below: Amethyst with minor calcite, Artigas, Uruguay. Specimen is 185mm wide.