Flinders, Victoria, is a well-know mineral locality, particularly zeolite minerals. There are actually a number of distinct localities, with different suites of minerals, within the Flinders area, but usually just referred to as “Flinders”. The best-known is Cairns Bay.

Earlier this week, Pater Hall and I went to look at another one of the localities, West Head. This area is just to the south of the Flinders township, and is the easternmost locality in the area. We first walked out to the western-facing side, and were able to see a few signs of zeolites, a couple of dykes, and lots of ironstone. The dyke rocks are a lighter greenish colour, quite different to most of the surrounding black basalt.

On the eastern side, there was one main dyke, and this hosted a few minerals including black prismatic crystals of kaersutite. And there was lots more ironstone. This occurs on the perimeter of the dykes, as thin veins cutting through the basalt platform, and as masses.

Nearby, there were some very oxidised (rusty) rocks with zeolites, but mostly too weathered.

The ironstone occurrence is certainly different to other basalt areas along the coast, both here at Flinders, and over on Phillip Island. So why is it there, and how does it form? I’m not an expert, so if anyone has a better explanation, please share it in the comments.

The ironstone is likely related to the interaction between the hot intrusive dykes and the surrounding basalt, as well as the subsequent alteration of the basalt. The hot, slightly acidic hydrothermal fluids are efficient at leaching iron (Fe) and other elements from the surrounding basalt and the dyke rock itself. As these hydrothermal fluids circulate through the rocks (especially at the dyke margins) and encounter cooler, chemically different areas, the conditions become less favourable for dissolved iron. The iron in the fluids often precipitates as iron oxides and hydroxides (eg: hematite, goethite, and “limonite”) within fractures, along the dyke contacts, and in porous areas of the basalt. The surface weathering can contribute to the formation and concentration of ironstone. Water can leach out more soluble minerals, further concentrating iron oxides as a residual deposit, especially in the upper layers of the basalt profile, essentially forming a laterite deposit.

The rusty appearance of the nearby rocks is a very clear visual indicator of significant oxidation of Fe²⁺.

I will share more photos of the area, and the minerals, in an upcoming issue of the Monthly Mineral Chronicles.

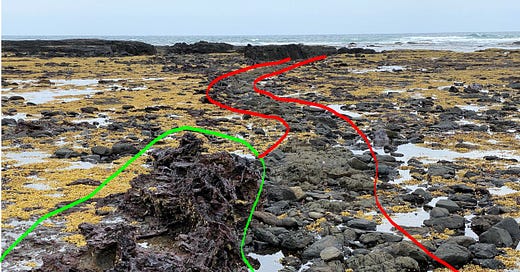

Below: The main dyke (highlighted in red) on the western side with a mass of ironstone (highlighted in green). This dyke was particularly interesting with its meandering route.

Below: One of the dykes on the eastern side of West Head. This one a bit straighter, but interestingly varies in width.

Below: Black kaersutite phenocryst in dyke rock. This crystal is about 50 to 60mm long.

Steve, how did you know confidently the phenocryst is kaersutite ? What gave it away..? As ever, I'm overwhelmed and perplexed when it comes to ID'ing. :-)) Marg

What a great name for someone! The name’s Rocks. Rusty Rocks.